VII. Echo and UDCA signals. The hi-lo carding today is called “Echo”. The signal was born in the whist age, and it’s the very first convention of our game; at first it was called Blue Peter; the name could originate (it’s not certain) from a navy signal, for the flag which is raised when a ship leaves port. The whist is played by pairs as bridge, but without dummy and auction; everyone plays his own cards, and the trump suit is determined turning up the last card of the deal; any trick over the sixth is worth one point. In whist the key question is which side holds more high cards; playing trump early in order to save its high cards is in that pair’s interest; the unnatural play of a higher pip card instead of a lower one when following suit is the signal to shift to trump.

VII. Echo and UDCA signals. The hi-lo carding today is called “Echo”. The signal was born in the whist age, and it’s the very first convention of our game; at first it was called Blue Peter; the name could originate (it’s not certain) from a navy signal, for the flag which is raised when a ship leaves port. The whist is played by pairs as bridge, but without dummy and auction; everyone plays his own cards, and the trump suit is determined turning up the last card of the deal; any trick over the sixth is worth one point. In whist the key question is which side holds more high cards; playing trump early in order to save its high cards is in that pair’s interest; the unnatural play of a higher pip card instead of a lower one when following suit is the signal to shift to trump.

It’s important to point out one distinction: playing a 3 rather than a 2 has no intrinsic worth, it makes no difference in the outcome of a trick. But playing the 3 first and the 2 after violates the principle of economy, and every violation of principles must raise questions about its hidden meaning.

The Official Encyclopedia attributes the Blue Peter to Lord Henry Bentinck, (1774-1839), dating it to 1834. Henry was cousin of the better known general William Bentinck, who in the spring 1814 led successfully a naval raid in Tuscany against the French, who then held the northern Tuscany and Genoa. The Bentinck were ancestors of Elizabeth II.

In the first decade of the 20th Century, one of the strongest player of the time, Joseph Bowne Elwell, transplanted the Blue Peter into the auction bridge, the third rung in the ladder of bridge’s evolution. (The first rung was whist, born in late 15th Century, followed by bridge-whist in the 1870s; auction bridge came in 1903; and eventually contract bridge in 1925. For articles on these games, search Neapolitan Club for the above key words). Auction bridge, with bidding and a dummy, eliminated the need for signals of general strength or commands to play trumps. Because of that, Elwell adapted the old device to a new purpose: signalling the capacity to take a trick on the third round of the suit. On the ace lead, a unnecessary high card response signalled doubleton or queen in the suit.

Joseph B. Elwell died at age 47, killed by a shot from a revolver inside his home on the evening of 10 June 1920. The husband of his mistress was suspected, but no evidence was found and the murderer was never identified. The mystery writer S. S. Van Dine took the idea of the Elwell case for his first detective Philo Vance novel, The Benson Murder Case” (1926. First edition by Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York).

But the Echo has a drawback: we are not always rich enough to get rid of a 9, a card which might win a trick or protect an honour. A less wasteful mode of carding is Upside Down Count Attitude (UDCA), which is the opposite of Echo: High-Low discourages or gives odd count. By this mode, in Attitude the 9 drops from a useless suit; in Count it comes from three or five card suits: in the former case it is almost useless; in the latter the next lower card is high enough to make for loss of the 9, giving a signal still sharp.

UDCA has advantage with an honour-small doubleton such as Kx, Qx, Jx, 10x. With Echo, there’s no chance to signal the doubleton without possibly wasting a potential winner; using UDCA, we can play the low card as an ordinary and correct signal, while retaining the possibility of sending a special signal with the honour.

The UDCA was first mentioned in 1937, in a Bridge World article by E. K. O’Brien. But it is thought to have been invented five years earlier, in 1932, by Karl Schneider (1904-1977). Schneider was one of the Austrian Foursome which won the world title in Hungary in 1937; French champion Roger Trezel called him “The most outstanding player I have ever met”.

VIII Honour leads as signals

In Standard Carding, the lead of an honour showes the lower touching honour an denies the upper one. An exception is the lead from A-K, where the ace asks for Attitude, the king for Count, then the leader has the chance to pick up the card according to the defensive signal best suited for his purposes. This does not apply in the case of ace-king doubleton, where the card led is always the ace. Examples (the card to lead is underlined):

AQJx, KQ(x) QJ10x, AJ10xx 109x, 109 (doubleton) AK (doubleton)

The problem emerges when the touching honours are ace, king and queen, as the following: KQxxxx, AKQxxxx, AKx. In the first of these three instances the lead must be the king, where the partner will respond with Count but without knowing whether the lead came from ace-king or king-queen. In the second case there’s another problem: what interests to leader is Count, not Attitude. But under certain circumstances, the lead of king from a long suit is at risk of being ruffed by partner, maybe losing a trump trick. And, if the shortage is in dummy too, the ace and queen are exposed to a possible ruffing finesse made easier because partner had shortened his trumps. In the third example, when the lead is by ace partner can’t know whether it was from A-K alone or with small cards (a frequent lead because it allows to a look at dummy while holding the lead), or from ace alone, by no means a rare lead.

Many of these ambiguities are resolved by the Rusinow Lead, invented by Sidney Rusinow. In Rusinow, the lead from two (or more) touching honours is always the second lower, except when they are alone. To understand the point, let’s take the examples we’ve just seen, leaving standard carding’s lead underlined and indicating the Rusinow treatment in bold-face.

AQJx, KQ(x), QJ10x, AJ10xx 109x, 109 (stiff, UDC), AK, KQxxxx, AKQxxxx, AKx.

Notice that, in Rusinow, the leader’s partner always knows that an ace lead denies the king but when it comes from stiff honours, a combination that standard doesn’t solve as well. The J-10 is the lowest combination where Rusinow applies; 10-9 or lower reverts to standard (or UDC) agreements.

Sidney Rusinow (Newark, NY, 1907-1953), invented his lead in the 1930s. Though it was endorsed by Ely Culbertson, the Rusinow lead was forbidden in the USA until 1964 (2001 Official Encyclopedia of Bridge).

IX. Flexibility 2

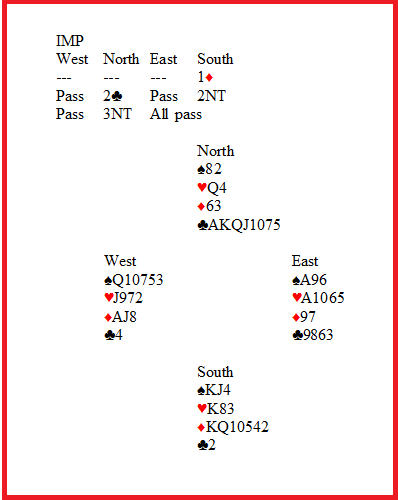

As we’ve indicated in the previous of these two articles on defensive signals, even with the most sophisticated tools it’s not always possible to send the desired signal. Here’s another example, taken from English writer Daniel Roth’s “Signal Success in Bridge” (1989, Victor Gollancz).

West led spade, East winning the ace and returning the suit. South lost the finesse and won the third round, then played ♥K; West played the ♥2, dummy the ♥4. What should East do? The problem for declarer (if he had problems and wasn’t trying to steal an overtrick, a case of little interest at IMPs), is that either he has only eight tricks or that he has no club with which to enter dummy. In both cases he’s trying to establish the ♥Q, whether as ninth trick or as entry. In the former case East must take and shift to diamond, in the latter he must duck. Partner’s carding ♥2 showed odd count, information that was useless and in any case incorrect because he held an even number of cards. East, he was a Life Master though, unluckily decided to duck.

West’s ♥2 may have looked wrong, but it wasn’t a mistake: he decided that information that needed to be passed was Count all right, but in clubs rather than hearts. Lacking the tools to give club count, he improvised, using improper ones. Had he been able to think out loud, here’s more or less what he had to say: Partner, count in hearts obviously isn’t important, so pretend that my count signal in hearts is really a count signal in clubs. Then… etc. Notice that the count was wrong for hearts, but right for the clubs he had. Also notice that the signal was very sharp, being the 2 a utmost card.

Philip Roth’s story ends here, but there is something to add: West had a difficult problem, however he needn’t masking his clubs in hearths. He could normally signal his entry in ♦A, he had the right tool for a normal – and imperious – signal by dropping the ♥J. This was obviously Suit Preference, with diamonds as the only suit he could sensibly be calling for. Beyond that, the ♥J resonates like the beat of kettledrums, while the ♥2 could slip away unnoticed, as it did. (West didn’t yet have count in hearts, and couldn’t check the “mistake.”)

X. Short system of leads and defensive signals

Kind and hierarchy: Count, Suit Preference, Attitude (C – SP – A).

Importance: Highest priority Count (it’s worth saying: “in doubt, it’s always a Count signal”).

Tools: spot cards from 2 to 9. Honours from 10 to ace are outstanding tools, usually for SP or A.

Mode: Upside Down Count Attitude (UDCA). Suit Preference is given discarding from suits that are not interesting.

Leads.

– Rusinow. Second ranking from touching honours down to J10. The rule doesn’t apply when leading on partner’s known suit nor from doubleton honours.

– Upside Down Count, but Attitude when leading on partner’s known suit; in this case low card shows honour from jack upward.

– 10-9 or 109x: by 9; 10932: by 2 (UDC)

Response. The response is according to the Norm (UDC), but a case: when partner leads a queen (usually from K-Q headed suit), and the jack isn’t visible, the response is in Attitude (UDA), encouraging when holding either jack or ace.

Return and Shift. After the lead of West, when East takes the lead and plays the same suit, the Norm doesn’t apply: East plays high from three or less cards originally held, plays low with four or more. In the Shift, that is when East plays a different suit, the Norm still stands.

Discarding. All Normal: discards deny interest and show the UD Count in the suit dropped.

Conclusions

This article can end with a sentence from Mark Horton’s book: Let’s make one thing clear, every defensive signal is merely an aid for the defenders, it is not a substitute for clear thinking. You cannot afford to play as if you are in a straight jacket, they are for mental patients not bridge players!

***

Paolo Enrico Garrisi

Many Thanks to Hanan Sher for his invaluable help.

The Defensive Signal: Part One »